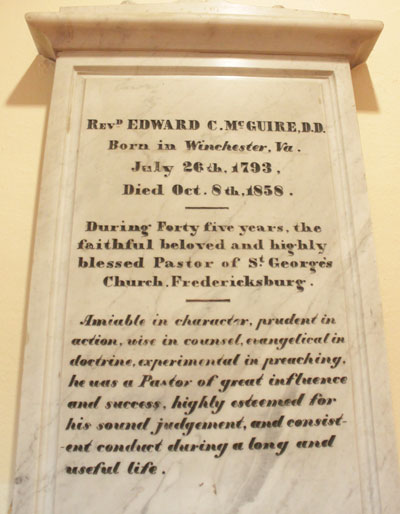

Edward McGuire is arguably the most important figure in St. George’s 300-year history. He served as rector for 45 years, 1813-1858, the longest in our history and served in all three St. George’s Church buildings (colonial church, 1815,1849) and helped to build two of them.

Church Builder

At his death, the newspapers wrote many accolades and focused on the numbers he brought to the Church. The Fredericksburg News wrote on October 12, 1858, wrote: “Under his faithful culture his congregation has greatly multiplied in numbers and flourished in all of its highest spiritual interests.” The Weekly Advertiser at the same time noted he had baptized a whole generation in his communion and increased the church from a mere handful to hundreds. From a small number when he arrived (13) the Church had grown to 259 communicants a year after his death.

The Poor

Another interest in McGuire was the condition of the poor. He was part of the Benevolent Society in 1817 to collect contributions through directly calling on people. The tone of the language applies to our time. The winter was harsh and funds that had been contributed earlier were nearly exhausted. “Provisions scarce and prices very high” “But little can be done at this time by the indigent to provide for themselves the necessities and comforts of life.”

Education

Within St. George’s, Christian education was one area that McGuire noted in reports to the Diocese which reported anywhere 3 to 5 Sunday Schools, reaching a high point of 350 “scholars” in 1846 taught by 30 teachers. The Episcopal Sunday School was the first church Sunday School established in this region in 1816. Sunday schools were part of the social framework of society, broader in scope than our own time, educating the poor in “useful knowledge” as well as “morality and genuine piety” and had arisen in England in the late 18th century. There were two departments – one for the 3R’s and the other to teach the scripture, the psalms and hymns. Faulkner Hall, constructed in 1823, just to the north of the current church building, was intended “for the accommodation of the Episcopal Sunday School and for other religious purposes.” In addition, Bible Classes were mentioned in reports to the Diocese as early as 1827 and by 1833, 60 to 70 attended.

John Washington, the Fredericksburg slave turned freeman and who grew up across the street at the former Farmers’ Bank (National Bank building), did not have a high opinion of the Sunday Schools in 1852. The schools were in the afternoon and the students were taught the catechism and “verses of the Bible were read to us by heart.” “I do not think much good resulted from this school for we was not permitted to learn the ABC’s or to spell” though he was sent other places where did he learn the skill.

McGuire’s influence extended in and beyond Fredericksburg, particularly in education. In 1816, he started a Female Academy for “young ladies” in those “branches of science which constitute a liberal and polite education.” He offered to provide boarding. In Fredericksburg, he was a trustee in the Female Charity School, examined their books and made appeals to relieve their “impoverished state of the funds” in 1823. He was also part of the original committee that supported the creation of the Fredericksburg Classical Academy and also became a trustee in that organization.

Outside of Fredericksburg, he was a member of the group that established the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria.

Slavery

From a contemporary perspective, one troublesome part of McGuire’s legacy in our time was his role as a slave owner. From 1818 to his death in 1858 he owned anywhere from 1 to 4 slaves though they were freed at his death. In 1837, when he owned 4 he was in the top 20% of slave owners in Fredericksburg. At the same time, owning at least one slave was a common practice – only 1 in 10 in 1818 did not own slaves.

Slaves used in the home were common in Fredericksburg, much more so that the Free Blacks which numbered 420 in Fredericksburg in 1860 (compared to over 1100 slaves). While there was a feeling after the revolution that gradual emancipation was promising for the 20 years after the Revolution, sentiments had changed by McGuire’s time due to slave revolts. Besides African Americans were viewed as inferior and those that had been freed were felt to be dangerous to society.

A year after he bought his first slave he became a manager in The American Colonization Society branch in Fredericksburg founded at St. George’s in 1819 which proposed setting up a colony that eventually became Liberia for free blacks. McGuire wrote in his diary that it was a “great and magnificent design”. McGuire saw it as transmitting religion to thousands in Africa who had not been exposed to religion as well and provided for gradual emancipation. Most religious groups believed that the assimilation of the two races in America was impossible and by forming a settlement in Africa as giving African Americans true equality. McGuire collected money at St. George’s for the society from 1819 to at least 1846. Moreover, he journeyed to the local counties, such as Culpeper pushing the scheme. St. George’s, in addition, sent two missionaries to Africa during his time.

McGuire also promoted African Americans at St. George’s. In the 1834 Diocesan Council, he mentioned the “spiritual improvement of coloured people.” He praised “recent endeavors to instruct them by preaching have been attended by the most encouraging indications of usefulness” though he noted a year later that progress had been “interrupted.” Trends improved. By 1846 he noted that 2 of 5 Sunday schools were composed of 80 “domestic servants.” and “often taught by the rector.” In Annual Convention, he noted 1 African American communicant.

Go to the right side (south) of the church for the marble plaque opposite McGuire’s for Reuben Thom.