Quick Tour Links

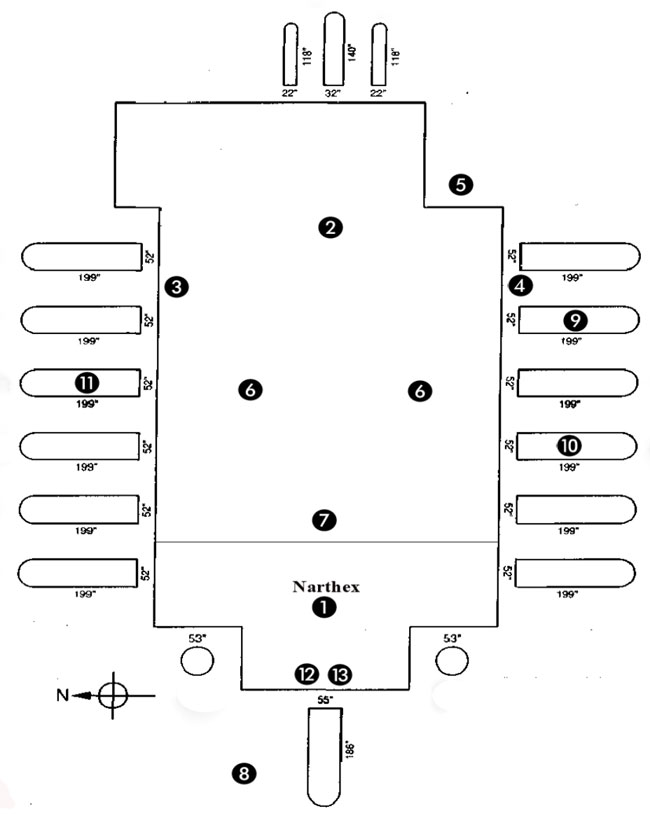

1. Narthex

2. Chancel

3. Plaque to Rev. Edward McGuire

4. Plaque to Reuben Thom

5. Plaque to Phillips Brooks

6. Pews

7. Organ

8. Architecture

9. Stained Glass Windows – “Angel of the Resurrection”

10. “Angel of Victory or Guardian of Medical Science”

11. “Road to Emmaus”

12. Meneely Bell

13. Clock, 1850

St. George’s role in the Civil War

- Narthex

You enter the church via one of the three double wooden doors which are in the Romanesque style with rounded arches as opposed to Gothic with pointed arches. They are symbolic of the trinity – Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Outside the front of the church, are three sets of steps. These steps were part of the current 1849 church and made out of Aquia Sandstone, mined 20 miles north of here on Government Island. During George Washington’s Presidency, Government Island was purchased by Pierre L’Enfant on behalf of the federal government in 1791 to provide stone to build the nation’s new capital city – Washington, D.C. Our steps were renovated in 2011 and 2012.

Directly inside the front doors is the narthex which has a slate floor. The Narthex is the vestibule of the church, a place to greet parishioners, a place of gathering. The church has a baptismal font given by Basil Gordon in 1829. It can set in the Narthex or closer to the front when we have a baptism.

On either side, in front or behind, there was decorative paint added during our renovation 2007-2011. The pattern just to the left of the center door leading into the main church imitates a pattern found on a 1906 photograph.

South is to your right, north to the left. In the north and the south ends of the narthex are the typical rounded, recessed arches that divide the narthex into three sections. In each of the two side sections is a stairway with black walnut wood that ascends to the gallery.

Enter the church through the middle door and proceed up the middle aisle to the chancel entrance where the pews end and the rail at the front begins.

- Chancel

The chancel is separated from the nave (the part where the congregation sits) by a communion rail. It has an altar in the center where the bread and wine are consecrated for the Eucharist, the main Episcopal service. To the right is the pulpit where the minister preaches.

To the left is a lectern for the reading of the scripture.

The chancel carries the symbols of our faith: (1) The font symbolizes our entry into the living Christ as members (arms, eyes, etc.) of his Body. This font can either be in front or in the narthex. (2) The lectern and pulpit symbolize the Word of God. (3) The altar table symbolizes our being fed by Christ’s life in bread and wine.

The chancel has changed throughout our history. The current chancel derives from the renovation, 2007-2011. Renovating the chancel was intended to place a focus on the Eucharist and several key symbols of our faith and to allow them to be better viewed by themselves and in relation to other symbols. There was also the desire to make the chancel less cluttered and open. The choir and organ were moved to the gallery from the chancel where they had been prior to 1925.

The reredos is a screen separating the chancel from the sacristy where the priest’s robe, the flowers are arranged and the bread and wine are prepared. The reredos originates from the latter part of the 19th century when the church shifted from a central large pulpit and Presbyterian influences to an earlier style derived from Catholicism – cross, candles, flower on the altar and vested clergy. It was restored in 2000 after a long period of storage.

The communion rail has 7 kneeling cushions completed from 1975-1978 under chairperson Ruby Harris. Designs were done by Mrs. Edmund Pendleton III. The symbols include Iris (Mary), Crown (Jesus as the King), Lamb of God (Jesus), Hand (God), Dove (Holy Spirit), seven gifts of the spirit, and the shield.

Above the chancel is the Ascension Window, a gift in 1885 in memory of Rev. Edward McGuire who served 45 years. The window is from Heidelberg, Germany. The Ascension took place 40 days after the Resurrection when Jesus led the disciples to Bethany. He raised his hands, blessed them and then was lifted up until a cloud took him out of their sight. This is shown in the window.

Go to the left side (north) of the church for the marble plaque.

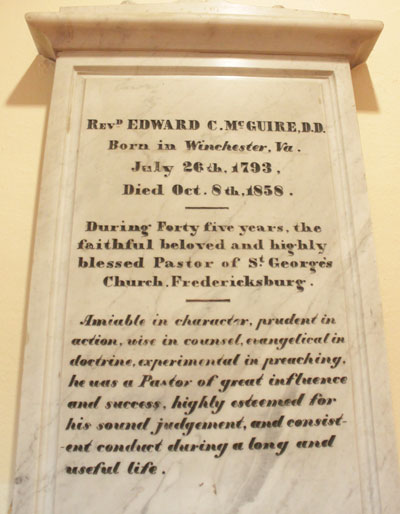

- Plaque to Rev. Edward McGuire

Edward McGuire is arguably the most important figure in St. George’s almost 300-year history. He served as rector for 45 years, 1813-1858, the longest in our history and served in all three St. George’s Church buildings and helped to build two of them. At his death, the newspapers wrote many accolades and focused on the numbers he brought to the Church. He is buried in our graveyard.

Go to the right side (south) of the church for the marble plaque opposite McGuire’s for Reuben Thom.

-

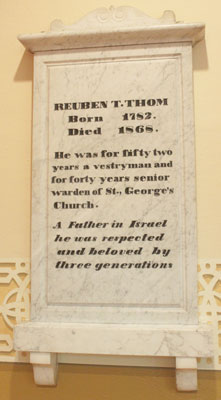

- Plaque to Reuben Thom

Reuben Thom was on the Vestry for 52 years and is the longest-serving Vestry member in our history. Remarkably he was senior warden for 40 of those 52 years. Like McGuire, he was buried in St. George’s graveyard and faces McGuire in death as he did in life. Thom worked as a postman and lived on Caroline Street in an 1822 home between George and William Street.

Move toward the chancel just to the right of the pulpit.

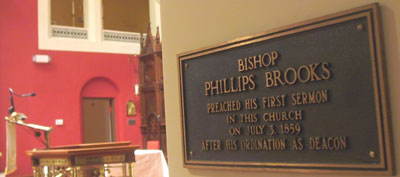

- Plaque to Phillips Brooks.

From the time he preached his first sermon at St. George’s in July 1859. Until his premature death in 1893 at age 57, Phillips Brooks never stopped preaching. He became the most famous Episcopal minister of his time at a time when the measure of a minister was his preaching through the sermon. Brooks is also famous for writing the words to “O Little Town of Bethlehem” in 1868. Turn around and look west to the back of the church for the pews and organ.

Look behind you for the pews and the organ

- Pews

St. George’s Pews are boxed pews, encased in paneling as opposed to open pews. It is likely that this was a holdover from the first St. George’s in the 1730s. Box pews provided privacy and allowed the family to sit together. The pews are original to the 1849 church. Due to their sturdy construction and the connection to the floor, they were not destroyed in the Civil War unlike some other churches in the area.

The current pews are original from the current 1849 church. The Church raised over $24,000 then ($500,000+ in today’s dollars) by selling 80% of the pews in 1849. At first, they were grained, gradually “darkened” after 1925 and finally painted in the early 1950s.

Pew ownership was demonstrated in a deed similar to real estate. Like real estate owners, pew owners were taxed beginning shortly after the Civil War, a practice that continued until 1943. Book racks and kneelers appeared on the pews in 1947 as a memorial to Edgar M. Young, junior warden.

- Organ

Organs have been a part of church worship since the colonial period. The current organ was dedicated in 2011, the last step in our renovation. The organ committee decided to replace the existing 1875 organ, with a custom-built instrument. After a review of organ builders, the committee settled on Parsons Organ Builders of Canandaigua, NY. During the design process, Parsons worked closely with our architect to incorporate design elements of St. George’s architecture into the organ case. The goal was to create an organ that blended well with the interior of our nave and looked like it had always been there.

These elements include: 1) Three large arches that reflect the Ascension window over the altar, 2) Columns with carved capitals similar to those in the sanctuary, 3) Lower case grillwork to match the grillwork in the gallery rails, and 4) A rich walnut case built in the Italianate style, with polished tin façade pipes.

The details of the organ, Parson Opus 29, are as follows: 3 Manual and Pedals, 44 ranks, 47 Stops and 2,667 pipes

- Architecture – There have been 3 St. George’s churches:

1st Church 1732-1815

This depiction of the first church was done by Dr. Michael Spencer of the Mary Washington Historic Preservation Dept.

The first church built in Fredericksburg was by action of the Vestry of St. George’s Parish at a meeting on March 13th, 1732. Col. Henry Willis contracted to build it and the new church at Mattapony for 150,000 lbs. of tobacco. The church was usable for services by the fall of 1734 and considered complete in 1735 when they paid the sexton. The new church was to be a frame building, 60′ x 24′, with ten windows 7′ x 3′ with shutters and 14’ walls.

George Washington knew this church, living across the river as a boy beginning at age 6 in 1738 and where he lived until age 18. He attended a school for several terms in a school run by St. George’s rector James Marye. However, he was never a member at St. George’s for he did not reside in Spotsylvania County (which included Fredericksburg). However, his brother.

But he was a frequent visitor to the town throughout his life, and in his diary, he recorded attendance here on at least two occasions – in August. 1770, and June 1788. At the time of the 1770 visit, his brother-in-law Fielding Lewis was serving as senior churchwarden, the highest lay position in the parish; his brother Charles and cousin Francis Thornton were vestry members. During the 1788 visit, the church became so crowded because of his presence that the congregation panicked. He picks up the story – “On Sunday we went to Church. The Congregation being alarmed (without cause) and supposg. the Gallery at the No. End was about to fall, were thrown into the utmost confusion; and in the precipitate retreat to the doors many got hurt.”

2nd Church 1815-1849

In 1812, the Vestry had already decided that because such major repairs were needed, a new Church would be built. On October 16, 1815, Bishop Richard Channing Moore consecrated the new Church which cost $11,000. The sale of the pews paid for the cost of building the Church. The 1843 insurance policy described the Church as 31′ x 72′ plus a Vestry room, 17’x 20’ behind the church.

The picture above is from a birds-eye view, a painting of Fredericksburg in the early 19th century from Ferry Farms across the Rappahannock River. The painting is from the Fredericksburg Museum. The second church is the large structure middle right with a slanting roof.

3rd church 1849 (current church)

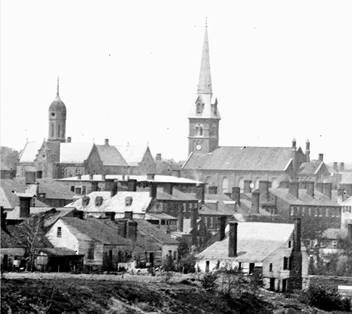

The photo is from 1863 taken across the Rappahannock River in Stafford by Timothy O’Sullivan, a Civil War photographer.

In 1843, the Vestry decided to raise money for a new Church. This decision was influenced by the fact that the 1814 Church had been built on a foundation of oak planks only three feet below ground in an effort to avoid graves in the Churchyard. This construction error caused cracks and breaks in the walls and actual sinking of the walls. The new Church was to be financed by the sale of pews as was with the 2nd church.

The church was designed and built by Robert Cary Long and H.R. Reynold of Baltimore and was larger than the other previous churches at 55’x95′. The church has a basilica plan with a wide center aisle and two side aisles. The side galleries were added when repairs were done after a fire in 1854. Forming and supporting the galleries on the second level are Corinthian columns each positioned directly over the columns on the first level. There is a decorative cast-iron balustrade running the whole length of the gallery on both sides.

In our 2007-2011 renovation, there was the revival of decorative paint inside the church. The thought became that the base colors of a church should be balanced with brighter colors to create interest and excitement. Paint should also show off the unique architectural features such as the columns and capital.

We move to the stained glass windows of Tiffany. The following window is the second window on the right or southern side (right).

- Stained Glass Windows— “Angel of the Resurrection”, 1914

The stained glass windows along the sides of the nave were added between 1907 and 1917 except for one in 1943. This was the era of Louis Comfort Tiffany He patented opalescent glass which acquired a much wider range of tonalities, textures, densities, and lines by using chemicals. We have 3 Tiffany windows which are part of this tour.

The above window, “Angel of the Resurrection” is based on John 11:26. Jesus is speaking with Martha in Bethany, consoling her and is trying to connect the resurrection with the present.

The angel announced Jesus’ resurrection in the Gospels. In this window, the angel is standing in a field of snow-white lilies, clad in robes of pink. The windows show Tiffany’s work in drapery glass for the angel’s robes that are close to fabric folds. Tiffany’s use of glass plays well with the sun which strikes the window in the morning hours. It accentuates the paint and enamel to the face and hands. The yellow-streaked, sun-dappled clouds are a dawn sky, a common metaphor for rebirth.

More on the Angel of the Resurrection

The next window is the 4th on the right or southern side.

- “Angel of Victory or Guardian of Medical Science”, 1917

The angel is holding palms which symbolizes the victory of the triumphant march into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday and the victory over death. The folds in the robe is another use of drapery glass. The angel is surrounded by opalescent glass in many different shapes with shades of greens, blues, and purple. This creates a variety of colors throughout the day as sunlight changes.

The next window is the 3rd on the left or northern side.

- “Road to Emmaus”, 1912

The story of this window is from Luke 24:13–35. In the image, Cleopas and an unnamed companion encounter the risen Christ on the road to Emmaus about seven miles from Jerusalem. The men are shocked that anyone could have been in Jerusalem and had not known of the events that have happened there. “Abide with us,” they ask the unrecognized stranger, “for it is toward evening, and the day is far spent.” It was not until they offered Him hospitality and He blessed and broke the bread that they recognized Him. He soon disappeared. They got up and returned at once to Jerusalem.

Christ ‘s robe was done with drapery glass. The background scenery shows purple confetti glass with solid glass representing the trees. The faces of the two companions show apprehension as they study the unknown man. The dark brown and green clothing contrasts with the lighter shades used in Christ’s robe. A unique feature of this window is found in the face of Christ. Without backlighting from the sun, the features of the face fade and are unrecognizable, but with the light of day, the features appear, making the identity of the “stranger” apparent.

The steeple with the bell and clock are outside the big red doors.

- Meneely Bell, 1858

Within the first 10 years of its life, St. George’s 3rd church added a clock and bell to its steeple. The bell and clock are best seen from the graveyard outside the church.

The current bell from the Meneely Bell Foundry in Troy NY was the second chosen for the new church as the first bell’s sound was deficient. The new bell was reported to weighing 8,000 pounds with a tone that was a “decided improvement” from the first one. (Actually, it weighed only 2,500 pounds). It would be the largest bell in town.

Bells were a primary means of communication – a way to summon the community for service, prayer or for special events, a wedding or funeral.

“In August 1789, Mary[Washington, George Washington’s mother] stopped speaking for fifteen days, and during her last five days, she slept or was in a coma. On Mary’s death, August 25, her family paid the town crier, Joseph Berry, to toll the bell for her at St. George’s Church. He would have rung it two times because a woman had died and then once for every year of her age.” (From the Widow Washington – Martha Saxton)

- Clock, 1850

Unlike our bell, the clock was not bought for the new St. George’s building in 1849. The Daily Star wrote it was installed by William H. White, a clockmaker in town around 1838. By May 1850 the clock was placed in the tower of St. George’s.

A city/church arrangement for the clock was a marriage of convenience for a city that wanted a clock but without its own location to house it. Both the church and the city were involved in the clock. It was the city’s clock; they would pay the maintenance and upkeep but the Church provided support. One of the church sexton’s duties was to serve as the clock “tender”. At first, the city appointed a “winder” and then contracted out the maintenance work.

We can’t conclude a tour without discussing St. George’s role in the Civil War.

St. George’s in the Civil War—1861-1865

St. George’s was a strategically located building in the center of Fredericksburg that could be co-opted for a variety of purposes. St. George’s was closed from Nov. 1862 for two years as forces prepared for battle. The town was sacked during the battle but the church remained pretty much intact. Even while closed for services, the Church played three roles in the war – first as a fortress in 1862 on December 11 before the main battle of December 13, 1862, then as a center of revival in the spring of 1863 and also as a hospital in both 1862 and 1864.

A description from a minister described the revival services here in 1863 – “Long before the appointed hour the spacious Episcopal church, kindly tendered for the purpose by its rector, is filled—nay, packed—to its utmost capacity—lower floor, galleries, aisles, chancel, pulpit-steps, and vestibule—while hundreds turn disappointed away, unable to find even standing room.” As many as 1,500 were reported attending one service.

In 1862, the largest hospital was at St. George’s and was the brigade hospital for the famed Irish Brigade. Major General St. Clair Augustin Mulholland in his memoir of the Pa. 116th Regiment describes the scene in today’s Sydnor Hall, below the nave floor: “In the lecture room of the Episcopal church eight operating tables were in full blast, the floor was densely packed with men whose limbs were crushed, fractured and torn.”

Two years later it was an evacuation point with the hospitals functioning to sustain federal wounded until they could be transported back to Washington by train or boat. Fredericksburg soon became a “City of Hospitals”. St. George’s was the only church whose pews survived since they were fixed, nailed down in place and not easily removed. In the Church the following scene was recorded by James Bowen in the History of the Thirty-Seventh Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers: “In the Episcopal Church a nurse is bolstering up a wounded officer in the area behind the altar. Men are lying in the pews, on the seats, on the floor, on boards on the top of the pews. Two candles in the spacious building throw their feeble rays into the dark recesses, faintly disclosing the recumbent forms.”

Communion set stolen! On Dec. 12, Federal troops occupied the town. St. George’s sexton Washington Wright, who was a free black on the church staff, noticed four Union soldiers at the altar. Instead of praying, Wright saw they were stealing the four-piece engraved sterling silver communion service that had been in use since 1827. Wright pursued them from the church and was able to recover one cup from a soldier he caught. It took 69 years until 1931 to get all 4 pieces back together, the last piece bought by the church for $50.

Few Churches in the war enjoyed such a varied role. While the church could be repaired and the communion silver recovered, the Vestry minutes from 1817 to early 1865 were sent to Richmond for safekeeping but presumed lost in the burning of Richmond in April 1865.