St. George’s in the Civil War—1861-1865

St. George’s was a strategically located building in the center of Fredericksburg that could be co-opted for a variety of purposes. St. George’s was closed from Nov. 1862 for two years as forces prepared for battle. The town was sacked during the battle but the church remained pretty much intact. Even while closed for services, the Church played three roles in the war – first as a fortress in 1862 on December 11 before the main battle of December 13, 1862, then as a center of revival in the spring of 1863 and also as a hospital in both 1862 and 1864.

The battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862 played havoc with Fredericksburg.

On Dec. 11 the church as in the middle of the Federal effort to land in Fredericksburg from the Rappahannock River. A ferocious Union bombardment began around 12:30 pm with over 150 cannon line along Stafford Heights. After two hours between twenty-five and forty buildings were badly burned. Still, over the day, the Confederates had delayed the Federal crossing for 8 hours until approximately 2:30 pm.

Union crossing the Rappahannock River

A Union artillerist describes a companion soldier’s attempt to destroy St. George’s clock:

“An officer of…[another] battery…remarked that the first shot he put into the city should pass through the clock; in fact, he proposed to breach the wail in such a way that the clock would fall-into the body of the church.” He explained that he felt impelled to this act through a sense of predestined responsibility..

“As many guns as could be brought to bear opened upon the city with a murderous, deafening roar. Remembering the threat against the tower and clock…I watched through a glass for their destruction, but the hands still moved on….

“Asking my friend…why he had failed in his threatened demolition…he replied that he watched the first shot he fired at it flying, as he thought, straight for the mark, but that before reaching the dial the shell visibly swerved to the right and only clipped a comer of the tower. The second shot was never aimed at the clock at all. He said he experienced such a change of feeling that nothing could have induced him to harm it.”

Later in the days, street fighting ensued moving south along Sophia and William Street in the city and finally late in the day to George St where St. George’s is located.

The 106th Pennsylvania led the Union advance south along Sophia Street toward the junction of Sophia Street and William Street, supported by the 72nd Pennsylvania and 42nd New York and surprised the Confederates. They moved to Caroline plunged into an unprepared flank of the 21st Miss and trapped 21 prisoners and forced them to retire to Princess Anne Street. The action moved to St. George’s. As Frank A O’Reilly writes The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock, “Mississippians entered houses and fired from windows commanding William and George Street. Some of the Confederates took over Saint George’s Episcopal Church and probably the Presbyterian Church for a clear shot down George Street.”

“An account from the London Times of January 23, 1863, follows which provides a mention of St. George’s: “The first impression of those who rode into its streets, and who had witnessed the feu d’enfer which the Federal guns had poured upon it for hours upon Thursday, the 11th of December, was surprised that more damage had not been done. But this is explained by the fact that the Federals confined themselves almost entirely to solid round shot, and that very few shells were discharged into the town. Nevertheless a more pitiable devastation and destruction of property would be difficult to conceive. Whole blocks of buildings have in many places been given to the flames. There is hardly a house through which at least one round-shot has not bored its way, and many are riddled through and through. The Baptist church is rent by a dozen great holes, while its neighbour, The Episcopalian Church, has escaped with one. Scarcely a spot can be found on the face of the houses which look toward the river which is not pockmarked by bullets. Everywhere the houses have been plundered from cellar to garret; all smaller articles of furniture carried off, all larger ones wantonly smashed. Not a drawer or chest but was forced open and ransacked. The streets were sprinkled with the remains of costly furniture dragged out of the houses in the direction of the pontoons stretched across the river. Many of the inhabitants clung to the town, and sheltered themselves during the shelling in cellars and basements.”

“Destruction of the Wallace Home” -corner of Caroline and William. Four of Wallace’s sons – all veterans of the Confederate armed forces – and two of his grandsons would become presidents of The National Bank. Two of the sons, Wistar And A. W Wallace did play major roles at St. George’s. Dr. Wallace and his wife are remembered in the stained glass window that Wistar Wallace dedicated – “Saint Paul Before Grippa”.

The Confederates advanced to their position along Marye’s heights and the main battle ensued on Dec. 13 with a sound defeat of the federals.

“Irish Brigade in Fredericksburg” – Don Troiani

In 1862, after the battle, the largest hospital was at St. George’s and was the brigade hospital for the famed Irish Brigade. Major General St. Clair Augustin Mulholland in his memoir of the Pa. 116th Regiment describes the scene in today’s Sydnor Hall, below the nave floor: “In the lecture room of the Episcopal church eight operating tables were in full blast, the floor was densely packed with men whose limbs were crushed, fractured and torn.”

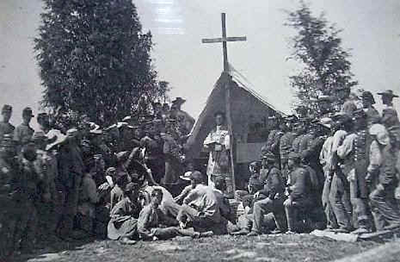

After the winter and before the next major battle at Chancellorsville, impromptu church services returned to St. George’s through a series of revival services

A description from a minister described the revival services here in 1863 – “Long before the appointed hour the spacious Episcopal church, kindly tendered for the purpose by its rector, is filled—nay, packed—to its utmost capacity—lower floor, galleries, aisles, chancel, pulpit-steps and vestibule—while hundreds turn disappointed away, unable to find even standing room.” As many as 1,500 were reported attending one service.

St. George’s in 1864

In 1864, St. George’s was a hospital again. Two years after the Battle of Fredericksburg it was an evacuation point with the hospitals functioning to sustain federal wounded until they could be transported back to Washington by train or boat. Fredericksburg soon became a “City of Hospitals” as described by historian John Hennessy:

“The first train of 813 wagons, carrying 7,000 wounded men, arrived on the evening of May 9, 1864. These caravans of the suffering would continue daily for two weeks until more than 26,000 men had passed through Fredericksburg.

“The wounded filled the streets and virtually every large building in town: churches, the theater “Citizens Hall,” Planter’s Hotel (where the butcher shop resides today), the courthouse on Princess Anne Street, warehouses on William Street, pharmacies and shops on Caroline, the great Woolen Mill north of town (the wall of its wheel well still stands along the new Heritage Trail).

St. George’s was the only church whose pews survived since they were fixed, nailed down in place and not easily removed. In the Church the following scene was recorded by James Bowen in the History of the Thirty-Seventh Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers: “In the Episcopal Church a nurse is bolstering up a wounded officer in the area behind the altar. Men are lying in the pews, on the seats, on the floor, on boards on the top of the pews. Two candles in the spacious building throw their feeble rays into the dark recesses, faintly disclosing the recumbent forms.”

Communion set stolen! On Dec. 12, Federal troops occupied the town. St. George’s sexton Washington Wright, who was a free black on the church staff, noticed four Union soldiers at the altar. Instead of praying, Wright saw they were stealing the four-piece engraved sterling silver communion service that had been in use since 1827. Wright pursued them from the church and was able to recover one cup from a soldier he caught. It took 69 years until 1931 to get all 4 pieces back together, the last piece bought by the church for $50.

Few Churches in the war enjoyed such a varied role. While the church could be repaired and the communion silver recovered, the Vestry minutes from 1817 to early 1865 were sent to Richmond for safekeeping but presumed lost in the burning of Richmond in April 1865.